Why continuous and mobile vital signs measurement of severely burned patients and during transports is the future

Healthcare in Australia differs from that in Germany in many respects. Of particular interest, Emergency Medicine is established as an independent specialist discipline. Emergency departments play a central role in hospitals and are often the largest departments that act as the hub for patient care. Patients are assessed and managed with the goal to discharge them back home where they can receive further ambulant care. These structures are also reflected in telemedicine and outpatient care, which are much more advanced in Australia than in Germany.

With this in mind, we spoke to Marc Schnekenburger, a specialist in emergency medicine and senior consultant at Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, about working as an emergency physician in Australia, the challenges involved and the planned applications of the cosinuss° in-ear sensor in emergency and retrieval medicine.

About the interview partner:

Marc Schnekenburger joined the ambulance service in 1994 through his community service. After studying medicine in Munich and spending several years in clinical practice, he moved to Melbourne in Australia in 2008 – initially for two years – to work at the Alfred Hospital. Today, he still lives there with his family and works as a specialist in emergency medicine and senior physician specialized in traumatology and severe burns.

Mr. Schnekenburger, how did you get into emergency medicine?

I came to emergency medicine by chance when I was doing my community service in the ambulance service. There I got to know the fascination of “human beings”. This included learning about physiology, pathophysiology and all the complex human processes. The aspect of working with people, often in difficult situations, was also compelling. Secondly, I enjoy working in a team. Emergency and critical care services is a fast-moving field – that really grabbed me and so I “got stuck” there. Then I did my professional training with the ambulance service. After that I went to Munich to study medicine and continued to work in the ambulance service during this time. Among other things, I worked in the emergency department at Schwabing Hospital. My focus was always on acute medicine: from pre-hospital care to the emergency room.

So why did you end up in Australia and stay there?

To answer the question, I must first explain that, in my opinion, Germany has a very good pre-hospital system.However, I was interested in what happens afterwards. I worked in the emergency department and was not able to experience the whole spectrum of Emergency Medicine as practiced in many other countries. In these countries the emergency physician is on an equal footing with other specialists such as internists, surgeons or radiologists. At the time, Germany only offered me limited opportunities in this field.. Combined with my desire to travel, I started looking for an English-speaking country in 2005. England didn’t seem that attractive to me, and the USA was scenic, but politically not inviting. I ended up in Australia in 2008. Initially it was supposed to be a two-year experience, but 16 years later we are still here in Melbourne.

How can we imagine your day-to-day work as an emergency physician in Australia and what is different from Germany?

Everyone has an idea of emergency medicine, as most people have certainly been to hospital before. In Germany, you walk in through a door and are directed left, right, straight ahead – depending on what problem you have or which specialty you fit into, e.g. children, pregnant women, foot injury, etc. In Germany, you are usually guided through the system in this way, depending on the complaint.

Here in Australia, emergency medicine in the hospital is the hub. All cases come in here. There is only a distinction according to urgency, i.e. someone who is limping and has a sprained ankle obviously doesn’t have the same urgency as someone who comes in with chest pain with a suspected heart attack. We have very large emergency departments here in Australia that aim not only to admit people to hospital, but to diagnose patients, create a treatment plan and, if possible, send them back to their own environment with local care. Together with intensive care medicine, emergency medicine is the youngest specialist discipline. However, as our emergency departments are quite big units, there is a very large group of specialists and as a result, emergency medicine is now the largest specialty in Australia.

To get an insight into the emergency departments at the Alfred Hospital: We are comparable to a German university hospital. However, we do not have an obstetrics or pediatric department. However, if cases from these areas do come to us, we also treat them. We have 80 beds in the emergency department. These are divided into “fast track”, which includes for example, minor injuries that require stitches, broken bones and simple internal medicine cases. The central area for more serious patients with around 40 monitoring beds makes up the majority. We also have a total of nine shock rooms. We have a “short stay” department where patients can be admitted for up to 24 hours avoiding a full hospital admission. We also have six acute psychiatric beds.

In principle, we work a three-shift model plus shifts in between. For example, there are around five senior physicians and five to ten doctors in training on a morning shift. There are also staff from other disciplines: Pharmacists, physiotherapists and nurse practitioners. We work together with many other departments here. Then there are all the nursing staff.

In Australia, medical care is very centralized due to the size of the country. In the state of Victoria, for example, with a population of almost seven million, we only have two hospitals for major trauma. This means that all cases that can be brought to us within an hour may have to travel past three other hospitals because they don’t have the resources to care for them. For severe burns, we are actually the only hospital here in Victoria. If they are further away, these patients are first treated locally and then brought here by ambulance, helicopter or plane, depending on the distance. Other services such as ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for external support of heart and lung function) are also centrally provided .

How well equipped is the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne compared to other hospitals in Australia?

Our hospital is particularly well equipped. For example, there are only two trauma centers in Victoria. We have around 1,500 polytrauma cases per year – so the equipment and setting has to be just right. This includes five trauma rooms for seriously injured patients. It doesn’t get any better than this in Australia. The Alfred Hospital is the largest center in Australia. The level of care in regional hospitals is similar to that in Germany. However, medical care in Germany is highly technical. I only realized that when I was abroad. The same applies to pharmaceuticals. Not everything that is available in Germany is available here. The regulatory and approval periods are generally somewhat stringent and longer here.

How advanced is telemedicine in Australia?

Many new innovations and developments often take their time before being established in Australia. Yet, other developments like telemedicine are very advanced. It has its origins in the Flying Doctors, which were founded in the 1920s (note: Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia (RFDS)). Due to the great distances involved and the need to provide care in remote regions, medical care via telephone or radio played a very important role back then. So people were open to the whole thing very early on. My impression is that telemedicine is more widespread in Australia today than in Germany.

A team of Flying Doctors prepares a patient for evacuation and transportation (Credit: Royal Flying Doctor Service)

Can you give specific examples from telemedicine?

Yes, for example, there are regions here that are three to four hours by car from the nearest regional hospital. In this hospital, there may only be a GP or a nurse. Already more than ten years ago, we had video conferencing so that we could see the patients and support the team, which has less experience with the most critically ill. This has been established in New South Wales, for example, for over ten years.

The coronavirus pandemic has led to further developments and new projects have emerged that are still running today. For example, emergency consultants are on the phone 24 hours a day to support the ambulance services, with the aim of being able to keep patients home. Nursing homes are also supported with the purpose of leaving and caring for elderly patients on site.

In our hospital, for example, there are also doctors who provide remote support to various regional hospitals with patients who may have cardiac problems. For example, the doctors or medical staff can send the ECGs to our specialists so that they can help with the assessment. The aim of all these telemedicine measures is to be able to assess and sort out as far as possible who needs to be brought to us in Melbourne and who can stay regionally.

Are you also active in telemedical consulting yourself?

Yes, I also have points of contact with it. For example, when I’m in the emergency department tonight, I’m the only consultant. If telemedical inquiries come in during this period, mostly cardiology inquiries, then I will probably make the call or one of the doctors in specialist training will. I personally like doing this because I think it’s a great way to support the smaller regions and avoid unnecessary transportation.

I also have points of contact with telemedicine in air rescue and retrieval medicine when you fly to a hospital and have to communicate with the staff there in advance. However, there is usually a separate team that has already started and coordinated the telemedical measures in advance.

This is particularly relevant for telemedicine: How good is the network coverage in Australia, especially in very rural regions?

What started here with radio technology 100 years ago is now very well developed. Even whenI’m in the outback, I have 4G or even 5G in many regions. Australia is at the forefront when it comes to good data transmission. Often even better than in some parts of central Munich.

You have a lot to do with severely burned patients in the field of emergency medicine. What is particularly important to bear in mind when dealing with these patients?

If more than 20% of the body surface is burned, the patient is considered severely burned. Major burns are a special group of patients. The care of these patients is provided in a centralized system, similar to Germany. All those affected in the state of Victoria are treated at the Alfred Hospital. Incidentally, in my opinion, the care of severely burned patients is also very well developed in Germany.

Major burns are a small patient group, and it is often difficult to get staff with the necessary experience. Even though we are a very large center for severe burn patients, we see no more than 40 per year. These patients are critically ill and injured and therefore have more specific requirements than our ,standard patients’. The ‚standard‘ includes major trauma patients as well as internal medical conditions. The care follows a typical pattern. This involves, for example, securing the airway, breathing and stabilizing the circulation. These body systems are also frequently affected in severely burned patients, meaning that early assessment and stabilization is required. In addition, problems occur in this patient group that we do not normally see in other patients. This includes the fact that the injuries can be very painful. Many of these patients also need to be intubated and ventilated during the course of treatment. They also have pronounced problems with temperature regulation, as the skin barrier is impaired potentially over a large area. We don’t have this to the same extent with other patients, even if it can be a problem with major trauma patients.

Major burns patients often have a progressive course of disease. Fluid shift in severely burned patients occur over several hours, even after six, or 12 hours. During early stages of resuscitation in the Emergency Department we first have to stabilize these patients and then monitor them closely. This allows us to intervene early in the event of changes and give patients a good start to their usually very long hospital stays. Severe burns patients generally have the longest stays of all patient groups.

What values are usually monitored in these patients?

Similar to all patients who end up in the intensive care unit. It includes the vital parameters of oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and temperature. The latter is also closely monitored. We normally start with non-invasive measurements, for example using a finger clip or blood pressure cuff. Later, we move on to invasive measurements: for example, blood pressure is measured invasively in the artery on the wrist or temperature measurements via a bladder probe or in the oesophagus. It is important that all vital signs are measured closely and continuously. However, the extensive burns in severely burned patients often mean that some standard methods, such as ECG patches, finger pulse oximeters or blood pressure cuffs, no longer work well.

What does the category “burns” include?

Burns are usually caused by flames. Scalds also count as burns and are more typical in pediatrics. Burns also include chemical burns. Chemical-toxic injuries are much rarer, but are also treated in the severe burns center. Ultimately, these are all serious skin injuries. However, patients with other serious dermatological conditions in which the skin peels off also end up at the Alfred Hospital.

Another focus of your work is retrieval medicine. Can you tell us more about this?

In Germany, retrieval medicine is most comparable to “interhospital intensive care transport“. It involves the rescue or retrieval of seriously injured or sick people from regions with low resources. I work for the Flying Doctors in Dubbo, a town with a population of around 40,000. Dubbo is a supra-regional center where everything is available. But it is also four to five hours away from the city of Sydney. If you drive further inland from this small town, it’s pretty much all outback. Medical care is already severely limited there. Firstly, in terms of staff. Although there are general practitioners or nursing staff who have a lot of general skills, they reach their limits when it comes to treating seriously injured patients. This also includes technical components. For example, there are no laboratories, and it is often not possible to take blood tests or only limited “point of care” measurements. In some cases there is no X-ray machine, no CT. Also no blood products, no intensive care units. There are many places like this in Australia. This is why retrieval medicine has become established, especially for the care of the seriously injured. This is how it usually works: In an emergency, the Flying Doctors are alerted at an early stage. The patient is stabilized on site using the equipment that is available or that they bring with them. This is one of the biggest challenges. A Flying Doctors aircraft is essentially a flying intensive care unit. We have all the equipment and medication that you would expect to find in a German ambulance, and sometimes even more. The initial aim is always to stabilize the patient and fly them back to the “high resource system”. Either to the nearest regional hospital, if this is sufficient, or to one of the major centers such as Melbourne, Sydney or Brisbane.

What are the biggest challenges here?

On the one hand, there is the distance or the time we have to bridge to the hospital. On the other hand, there is communication. As a rule, the doctors can connect to the coordination center via video call. Doctors from emergency medicine are responsible there, who can then put us in contact with the receiving hospital. This depends on the indication. However, the system is problematic for neurosurgical problems, such as a brain bleeding, because we often don’t know what the exact findings are as a CT is not available. In this case, we provide an overview and expected arrival time with the specialist team on the phone or via video call. We try not to waste too much time with these measures for critical patient transport, but always act in a forward-looking manner, i.e. to get to the destination, which may be several hours away, as quickly as possible and to maintain communication. We prepare the handover and treatment of the patient in the hospital in the best possible way. While we attempt to optimize distance and time, we can’t turn six hours into two. However, we can try to make the best possible use of that time period. What we would like to see optimized here: Many measures take time because we have to monitor patients closely. Many measuring devices and sensors attached to patients are connected with cables. All these cables have to be secured for transportation and everything has to be packed. After all, you don’t want to accidentally pull out any important lines for e.g. infusions. That’s why this “tangle of cables” takes a lot of time. It is still wishful thinking, but hopefully it will soon be a reality that we will have just one or two cables instead of many, allowing us to pack patients more quickly and worry less about cabling.

What means of transportation are used to transport patients?

Short distances are covered by ambulances. However, aircraft are usually used for retrieval medicine because the distances are much greater. If the helicopter flight time is more than one to two hours, an airplane is used. Helicopters mainly fly along the coasts. In the outback, mostly only airplanes.

How did you become aware of cosinuss° and the monitoring technology?

I became aware of cosinuss° through a colleague Dr. Boris Buck from Munich Among other things, he flies as a prehospital doctor with Martin Flugrettung and manages the “Martin 3” helicopter in Scharnstein (Austria). He has tested and used the cosinuss° system there together with other colleagues. The doctors there carry out many intensive care transports. Dr. Buck recognized the advantages of the cosinuss° system early on. I flew with him on my trip to Germany last year, received a theoretical introduction and then saw the sensor in practical use. I found the whole thing to be a great introduction. During my stay in Germany, I also visited the cosinuss° office in Munich to find out more about the technology, but also to talk about my experiences as an emergency doctor in Australia.

What projects do you have planned with the cosinuss° sensors?

“From tangled cables to wireless” – as already mentioned, this is the dream of many of us in emergency medicine. To get closer to this vision, I wanted to take a focused approach and start with the major burns patient group. I see the in-ear sensor as a good starting point here, as this is a very small group that often suffers from hypothermia. My plan is to integrate the sensor into the care of these patients. I have already submitted the necessary ethics application to be able to use the in-ear sensor in severely burned patients and to work out the advantages.

Ideally, the study protocol would then proceed as follows: when a severely burned patient comes to us at the Alfred Hospital, is resuscitated and wired up, the cosinuss° sensor should be inserted into the ear at the same time. In this way, a recording with the in-ear sensor should take place parallel to the recording of the standard vital parameters. The focus should be on continuous, non-invasive temperature measurement. In everyday clinical practice, the measurement of body temperature always lags somewhat behind the more “exciting” vital parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation. In my opinion, there is less focus on body temperature. However, I think that continuous measurement at a central location, such as the ear, can bring more attention to temperature measurement

So that would be the initial project. I would like to continue the project with a wider group ofpatients afterwards. I think that we can improve temperature management in severely burned patients. I would therefore like to conduct a prospective study to improve temperature maintenance by using the cosinuss° sensor and a new warming mat. This would also include an education program for both nurses and doctors. It should be a “bundle” of measures, so to speak, to improve temperature maintenance.

However, there are still disadvantages and challenges: it is a very small sensor in a big emergency department. A “controlled chaos”, so to speak, in which small things can get lost. I still have to think about how to ensure that the sensor doesn’t get lost. Many things in the emergency room or in the ambulance service disappear or are passed on. The two sensors I have here are therefore valuable assets. Perhaps the sensor could also be extended with a GPS sensor in the future in order to locate it.

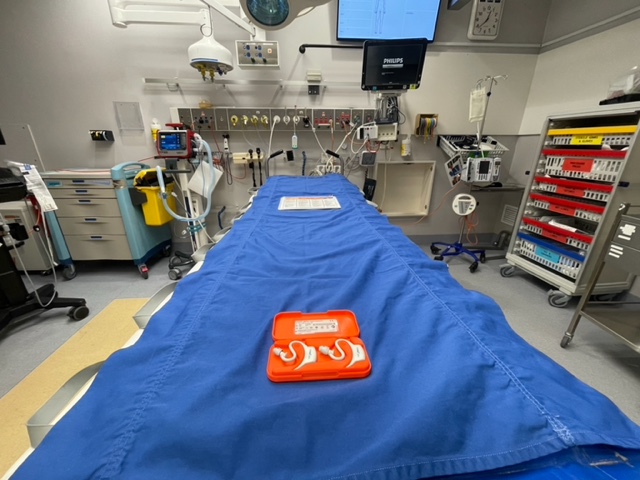

Two cosinuss° in-ear sensors c-med° alpha in the double charging box on a hospital bed at the Alfred Hospital (Melbourne, Australia).

Where within emergency and retrieval medicine do you see the greatest potential for the use of in-ear sensors and why?

I see a lot of potential. Based on my personal experience, I would like to use the sensor in retrieval medicine, for example.either in New South Wales with the Flying Doctors or in Victoria with ARV (Adult Retrieval Victoria). As already described, the sensor would give us a clear advantage when loading patients onto the aircraft: fewer cables.

There are many other possible applications that I can see: For example, for monitoring patients who are at home. But also in the emergency room or hospital. Here, it is particularly interesting to monitor patients continuously and wirelessly during transport from one area to another. Of course, these are examples of applications where a large number of patients need to be monitored. You don’t just need one or two sensors, but many. Again, you have to make sure that they don’t disappear. And, of course, integration into established monitoring systems would also have to be ensured so that the sensor is compatible with the central monitoring system.

What are your personal and professional plans: could you imagine using the expertise and experience you gained in Australia back in Germany at some point?

Yes, we have thought about it again and again and have had our ups and downs. We are very far away from our families here. In the beginning, that was the attraction. But every now and then, the distance meant that we considered returning. Germany was always an option for me – the life, the people, the society. However, emergency medicine has not attracted me so far and has not developed to the extent that I would have liked. However, I still really enjoy being in Germany, for example during my visit last year as part of a sabbatical.

In addition, everyday working life plays a very big role in my life at the moment. I think Australia is very attractive in this respect. It is much more normal here to work as a doctor in different hospitals and with different workloads – anything from 25% to 100% is possible. I didn’t know that from Germany in the medical field. It is also much easier to take time off, e.g. for exams or family reasons.

However, I could happily swap the weather in Australia for that in Bavaria.